How The Addams Family Created A Filmmaker Rift On The Set Of A Stephen King Classic

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Before Barry Sonnenfeld became a director with films like the “Addams Family” movies, “Get Shorty,” and “Men in Black,” he was a decorated cinematographer who often worked with The Coen Brothers, Danny DeVito, Penny Marshall, and on two of Rob Reiner’s most memorable films — “When Harry Met Sally…” and “Misery.” In Sonnenfeld’s new book, “Best Possible Place, Worst Possible Time: True Stories from a Career in Hollywood,” he described his role of cinematographer as a “friend of the director,” rather than just the director of photography. “I had as many opinions and ideas about editing, performance, or if the costumes looked worn-in enough, as I did about lighting or camera angles,” he wrote. It makes sense; the cinematographer is your first line of defense to make sure something looks right, so Sonnenfeld was often involved in areas that were “more the purview of the director.” He even joked that he “would truly hate me if I had to direct a movie with me as cinematographer.”

But this enthusiasm and keen eye made Sonnenfeld a great asset to directors. Rob Reiner often told Sonnenfeld he should direct, which he initially had no interest in doing. While Sonnenfeld and Reiner were working together on “Misery,” producer Scott Rudin offered Sonnenfeld to direct “The Addams Family.” The offer came “out of nowhere,” but as history would inform us, it was an offer that saved the film from becoming a disaster. Sonnenfeld loved his time on “The Addams Family” so much, that he turned down the chance to direct “Forrest Gump” to make the sequel, “Addams Family Values.” For what it’s worth, I think he made the right call.

After Sonnenfeld accepted the job, he returned to work on “Misery” and let Reiner know that he had been offered the chance to direct. “That was a mistake,” he wrote. “Now, instead of being the cinematographer, or ‘friend of the director,’ I was another director on the set, and no one, unless they’re brothers, wants that.”

Too many directors on set

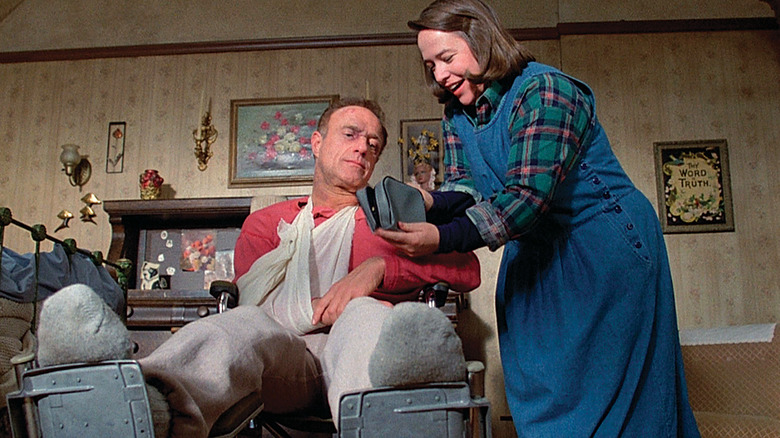

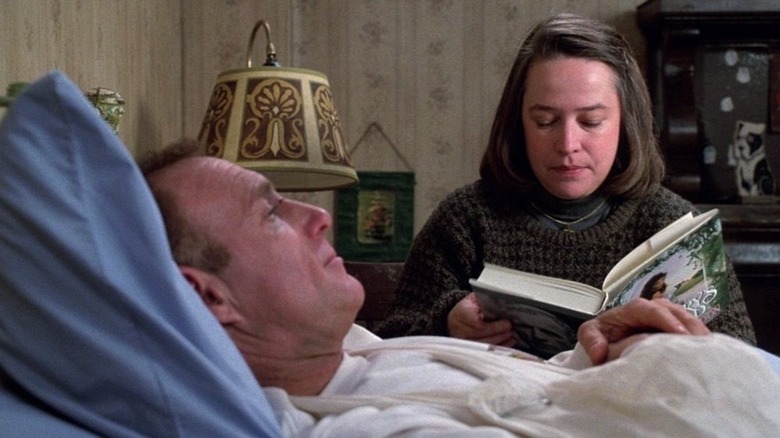

According to Barry Sonnenfeld, Rob Reiner isn’t too keen on filming stunts. It makes sense when you look at his filmography, which while boasting set-piece-heavy exceptions like “This is Spinal Tap” and “The Princess Bride,” is dominated by dramas or rom-coms about people existing in the world. That wasn’t the case on “Misery,” which included Kathy Bates hobbling James Caan, wrestling on the floor, and shoving burnt manuscript pages into Bates’ mouth. The latter scene was the last one filmed before lunch the day Reiner learned Sonnenfeld was going to be a director.

“The first shot back from our catered meal we set up a new camera angle to film Jimmy [Caan] and Kathy [Bates], burnt papers in her mouth, rolling into frame and continuing their struggle,” Sonnenfeld wrote. “I finished lighting, we called in the cast, and we shot one take.” Reiner called “cut, moving on,” which indicated that he was happy with the take and there wasn’t a need to do it again. Sonnenfeld gently suggested they do another one for safety, but Reiner cut him off. “It’s fine, Barry. Moving on,” Sonnenfeld recalled Reiner saying. He tried not to be too pushy but reminded him that this moment was a big one and one take meant there was nothing else to cut to. Reiner wasn’t having it. “Now I’m being annoying. The director has said three times he wants to move on and I’m still pushing. If I were the director, I would have fired me,” Sonnenfeld wrote. Reiner called the crew to the set and said:

“Baaaaaary thinks I should go again. Baaaaaary thinks it won’t cut together. But here’s the thing: There is only one director on the set. And it isn’t you [as he points to a random person], or you, or you or you or you. And it’s not Baaaaary. It’s me.”

Sonnenfeld agreed but pushed that he was worried the scenes shot before and after lunch wouldn’t cut together. Reiner asked the camera operator, Todd Henry, for his opinion. “Why don’t you look at playback?” Henry suggested. Reiner looked at the shots and realized Sonnenfeld was right, and called the crew to go again. “Rob and I did not speak to each other the last days of our shoot,” Sonnenfeld explained. “Nor for several years after that.”

Barry-ing the hatchet

Sonnenfeld recognizes that if the situation had been reversed, he would have been just as upset as Reiner was. As he wrote:

“Directing is really hard. There is constant pressure and anxiety. Every f***ing person thinks it’s their job to help you, and sometimes all you want is to be left alone to make your own decision even if it’s wrong. Hesitate on the set for more than two seconds and you’ll hear suggestions. You are never given any time to just think.”

Several years after Rob Reiner and Barry Sonnenfeld had stopped talking, the two were by happenstance both at Mr. Chow in Beverly Hills, a popular spot for directors to grab a bite to eat. Sonnenfeld was with his wife, who is very conflict-averse, but he wanted to say hello. “We love them, we miss them, and it’s going to be fine,” he recalled saying. “What if it isn’t?” his wife responded. “We’re not going to have a fight in Mr. Chow. I’m going over.” Sonnenfeld’s wife stayed at their table while he approached as if nothing had ever happened between them. “And just like that we were once again friends,” he wrote. “It has been over 30 years since we made up and not only are we still very close, Rob has optioned my memoir, ‘Barry Sonnenfeld, Call Your Mother,’ to see if we can make it into a movie.”

I can’t help but wonder who Reiner would cast to play himself.

Post Comment